Reconstructing Taylor's Genius

Paul Taylor Dance Company Artistic Director Michael Novak discusses how he brought back two Taylor masterpieces from the vault after 50 years.

This summer, Paul Taylor Dance Company returns to The Joyce, commemorating over 70 years of extraordinary dance with some of Taylor’s most beloved works, including Cloven Kingdom (1976), Polaris (1976), and Esplanade (1975). This year’s program embarks on an ambitious mission to bring two dances back to life after more than 50 years in the vault—Tablet (1960) and Churchyard (1969).

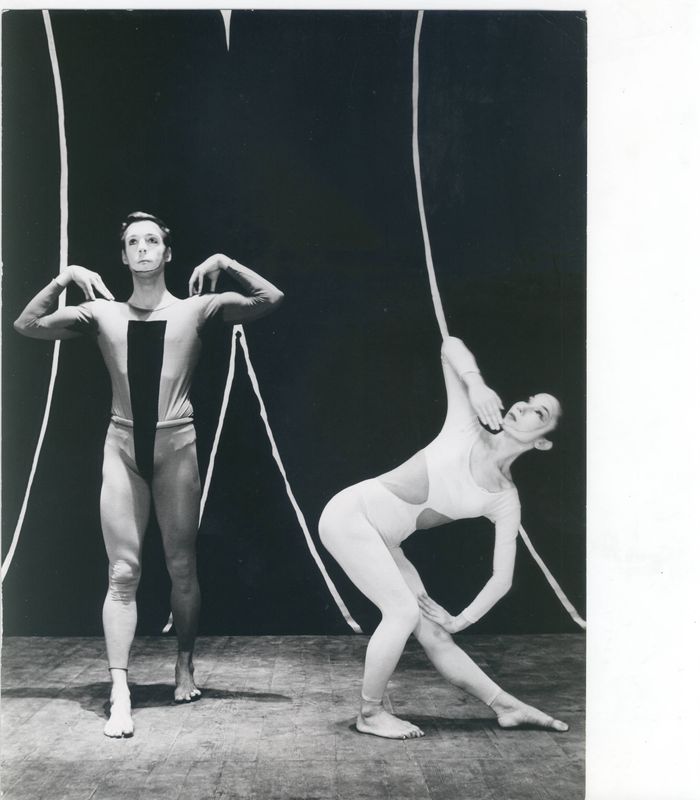

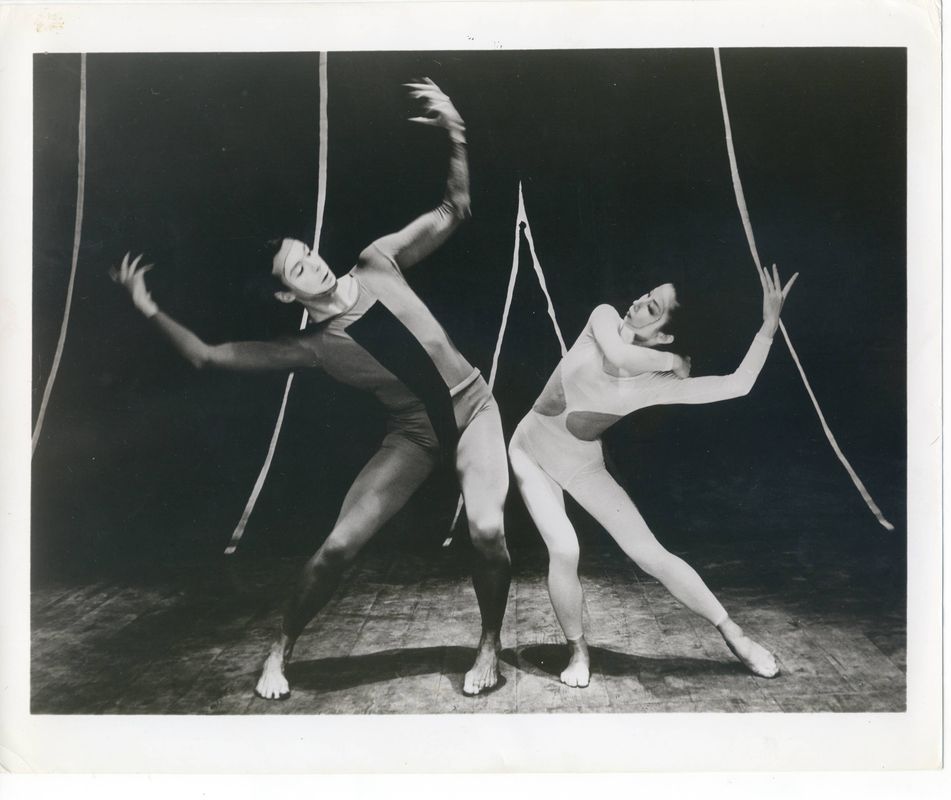

Tablet, choreographed by Paul Taylor with music by David Hollister, was first performed on July 1, 1960 at the Teatro Caio Melisso in Spoleto, Italy. Dance Magazine (1963) wrote that the piece “brims with inventiveness and play. [It’s both] accessible and ingratiating.” Churchyard features music by Cosmos Savage (based on authentic medieval pieces) and first premiered December 10, 1969 at New York City Center. Clement Crisp of The Financial Times (1970) described the work as “dark and beautiful…an evocation of the past that may well be a vision of the future.”

The reconstructions are being led by Artistic Director Michael Novak, in collaboration with a team of celebrated artists, including Rehearsal Director Bettie de Jong, Director of Education Carolyn Adams, and Nicolas Gunn, original cast members in Churchyard, Rehearsal Director Cathy McCann, Director of Licensing Richard Chen See, current Company member Madelyn Ho, M.D, and alumna Britt Swanson Cryer.

As the company prepares to reintroduce these pieces to the world, Novak reflects on the process of excavating the Taylor classics.

In this year’s programs, you’re bringing reconstructions of Tablet and Churchyard, pieces that haven’t been seen since the ‘70s! Why haven’t these works been revived since then?

Paul Taylor was a prolific choreographer and loved the unexpected. He was ever an iconoclast, and when asked what his favorite dance was, he would often say: “The next one.”

This forward-looking mindset kept his dancers and audiences guessing about what worlds would be conjured. Sometimes, dances he created went “into the vault” for a variety of reasons. I believe in taking a closer look at this, what dances we don’t see, and connecting them to what might be exciting for audiences of today.

What made these pieces groundbreaking when they premiered?

Tablet was created for Pina Bausch and Dan Wagoner. Most people don’t know that Pina danced for Paul Taylor, and here, he celebrates her angularity and infamous individuality. The dance also featured costumes, make-up, and a backdrop by Ellsworth Kelly—known for his exploration of color fields and minimalism. It’s a glorious example of the intersection of modern dance and American abstract art.

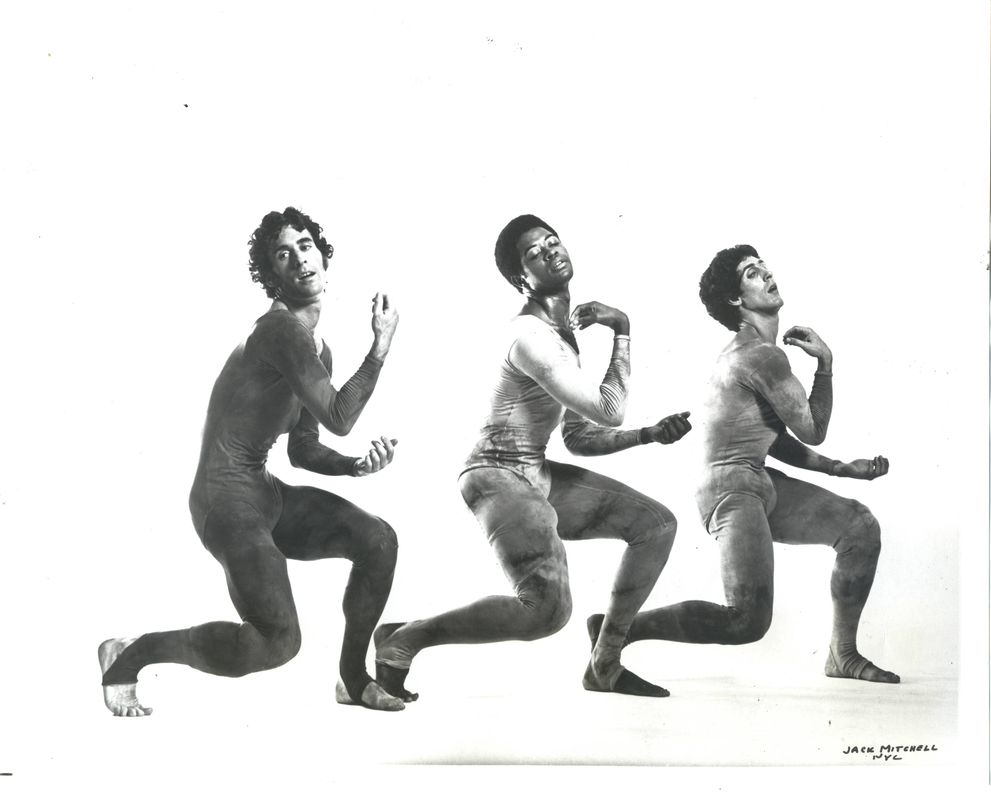

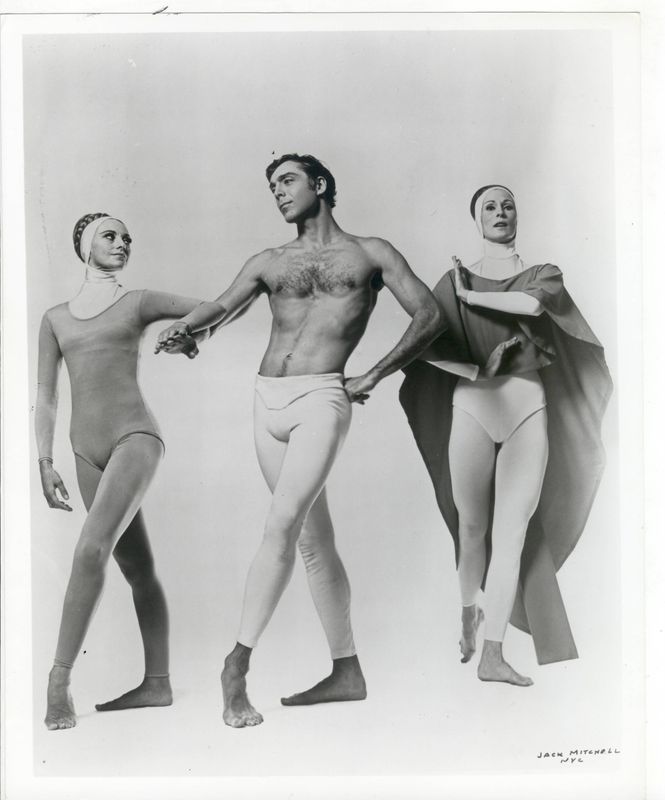

Churchyard is one of several dances that explores Paul’s fascination with duality, and it is rich in movement invention and diabolical partnering. Sometimes titled "Apocalypse", Churchyard is in two sections—"Sacred" and "Profane"—showing the eventual decay of angelic formalism, set against the soundscapes of medieval tunes and a disturbing score by Cosmos Savage.

What excites you about bringing these pieces to audiences today?

These dances haven’t been seen for over 50 years! They not only offer audiences a chance to see an early and radical side of Paul Taylor, but they also offer audiences an experience of Paul Taylor that feels brand new. It keeps the vastness of his genius front and center, even though he is no longer with us.

How did you go about selecting the members of the intergenerational reconstruction team? Why was it always important to you to work with such a diverse group?

Every generation of Taylor dancers carries with them an embodied wisdom: of Paul’s life; Paul’s evolution; the socio-cultural moment in which he was creating; who and what he was reacting to; how dances were perceived by audiences; and how audiences today are engaging with American dance. How beautiful that we can have dancers in their 20s working with dancers in their 90s and every decade in between.

Dance is an oral tradition. It is passed down in stories and memories. Steps and counts, and shapes are helpful structures, but alumni are the heartbeat that keeps the spirit true.

In describing the materials used to reconstruct these pieces, you list: archival video, Paul Taylor’s notebooks, Jennifer Tipton’s cue sheets, a small collection of photos, notes, and interviews from Paul’s collaborators. Can you briefly describe the process of assembling these materials and utilizing them in the reconstruction? How did each material help revive these pieces?

To say there is a great deal of research is an understatement. Hours upon hours go into reconstructing these dances, far before we even enter the studio with the Taylor Company. Rarely does one single element from our Archives hold all the answers. Sometimes the notebooks have faded, or the archival video is blurry. Perhaps the photos are inaccurate, or memories have faltered. Other times, the music changed over time, or Paul made adjustments to the choreography. All the elements have to be analyzed to reveal the dance. It takes significant detective work.

For example, the only video of Tablet we have in the Taylor Archives was flipped when it was transferred from the 16mm film. We only knew that because we cross-referenced it with Paul’s notebooks, which clearly broke down entrances, exits, and choreography. In Churchyard, our archival video is so blurry at times that only an original cast member’s memory could fill the gaps.

You describe the process of reconstruction to be a “profound journey.” What more have you learned about Taylor’s artistry through this process?

After all my years of working within Paul Taylor’s repertory, there are dances—and elements of them—that are nothing short of sheer genius. It comes down to craft, an uncanny eye, a thirst to be the iconoclast, heroic dancers and collaborators, and a passion to reveal all facets of the human condition…no matter how sacred or profane they may be.