A Legacy of Collaboration

Choreographer Lee Serle and Mateo López discuss their collaboration on the world premiere of Time again and working in conversation with Trisha Brown's legacy.

“I make order out of chaos, Bob makes chaos out of order, and where we meet is chaos.”- Trisha Brown

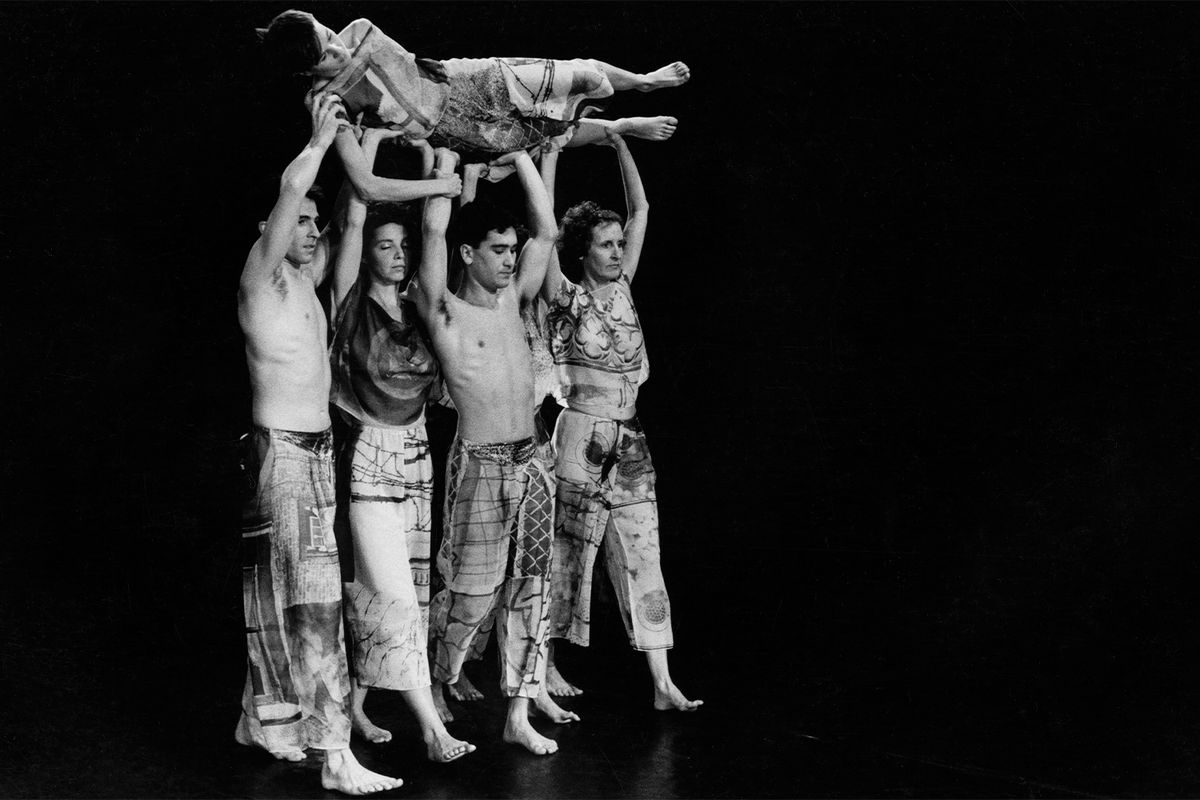

Labeled by The New York Times as the “innovative high priestess of postmodernist dance,” Trisha Brown is part of a lineage of artists who saw dance performance not as a siloed form, but as a conversation between set, sound, and movement. Her decades-long collaboration with painter and multidisciplinary artist Robert Rauschenberg illustrates her commitment to deep artistic collaboration across mediums.

Brown and Rauschenberg met when Judson Dance Theater (JDT) was established in the early 1960s. JDT was a collective of people who, through their collaboration, challenged artistic assumptions and questioned authority. At Judson, visual artists like Rauschenberg began to cross disciplines and experiment with performance. “We were a village,” Trisha Brown said reflecting on this time, “a collective. We didn’t have any of that judgemental kind of behavior and that allowed people to be very creative.” For decades, the two continued to work intimately on a wide variety of projects together that equally influenced, challenged, and inspired each other’s creative processes. Their collaboration put dance and art on equal footing.

In the 1997 Guggenheim Rauschenberg retrospective catalogue, Trisha Brown recalls,

“In our collaborations, I was a lightning rod for Bob’s theatrical projections. He described them to me as they occurred to him, often calling in the middle of the night. I would, in turn, picture the descriptions proffered, and in some cases choreograph with the spatial notion of the set he described to me in mind.”

Now, almost sixty years later, the Trisha Brown Dance Company (TBDC), of which Rauschenberg was the original chairman of the board, continues to embrace Trisha Brown’s commitment to multidisciplinary artistic collaboration. TBDC’s 2025 engagement at The Joyce features the world premiere of Lee Serle’s Time again, featuring set and visual design by Mateo López. Serle is the third choreographer to set work on the company other than Brown and his collaborative relationship with López mirrors that of Brown and Rauschenberg.

In an interview with the duo, learn more about their history as collaborators and how they continue to challenge and inspire each other.

Trisha Brown was famous for having deep collaborations with visual artists, specifically. So I'd love to learn more about your collaboration and where you two met.

LS: We met…Gosh, when was it? 2015?

ML: I think so, yeah.

LS: Yeah, yeah. We met in Italy, actually. At an event. And then, our first collaboration together was actually in Beirut in Lebanon with a theater collective there. And that's when we started to get to know each other and share our practices with each other. Shortly after that, around 2015 or 16, we were both living in New York at that time. And that's when we really started to become friends and become interested in each other's work–how it could eventuate and become an ongoing relationship.

ML: I was in New York because I was doing an exhibition at the Drawing Center. I wanted to do an installation with sculptural elements and drawing objects, and I decided to invite Lee to perform and activate the exhibition. I’d been curious about introducing the body into my practice to activate the works and make the exhibition space more alive and active. I guess that's how we started working together. And of course, this is all connected to my research I've been doing around that generation of artists from New York– the Trisha Brown generation. To me, they were radical in the way they practiced their work, the way they collaborated with the different disciplines. And I was very interested in that particular way of processing and working with different people. And I guess [this collaboration with Serle] started happening very naturally and now, we’re still here years after.

I find that really, really interesting. You hear a lot about being inspired by an artist's work, but it's really fun that you're so inspired by Trisha Brown's process. Can you talk a little bit more about both of your relationships to Trisha Brown and her work?

LS: I began working with Trisha Brown in 2010. It was part of a mentor protege arts initiative through Rolex. That facilitated this mentorship program and was my first experience of working with the company and being mentored by Trisha. I had, as a student, studied her work, so I was very aware of Trisha in the postmodern history of contemporary dance. And then, from 2010 to now, my connection with the company has been ongoing: as a dancer; the education director; I set work on tour; and now, I'm here being commissioned to make a work. So, it's been varied. The influence of Trisha and her work– her approach and process–is still very influential on me and how I work. It’s an interesting thing making your own work and, particularly, pay attention to lineage and honoring that. But also making sure that your personality and process and language emerges through as well. It's very hard to undo all of those learnings that you have when you've worked for somebody for such a long time.

ML: It’s part of the art history. These artists like Rauschenberg, Noguchi, and Cage worked and collaborated with dancers, musicians. They were a group of creative people creating work where there was specific line or discipline. I also, same as Lee, had a mentor part of the same program. A South African artist, William Kentridge, who was very open to collaborating on work in different fields. I guess he planted that seed and the curiosity to start exploring a more collaborative way of working instead of being inside the studio drawing and drawing and drawing. It forces you to think out of the box and quit your comfort zone. Then, I found myself having these amazing conversations with Lee and my works started transforming. I started changing the way I thought about what can happen inside the exhibition space. I realized that I wanted it to be more active, more, alive.

LS: Yeah. A lot of my previous work had been site specific. I hadn't made a lot of proscenium works and so I feel like that also really gelled with the two of us. What I was making and what Mateo were making was kind of bridging these two things, so they interlocked in a really kind of, yeah, organic and natural way because it was both of our interests, I suppose, to kind of merge those two practices together.

ML: And it opens a whole new world for my practice which is fascinating.

Absolutely! Now, you've been collaborating for so long since your first time working together. Is there a secret to having a long lasting relationship in this way?

LS: Well, you have to like each other haha. I can just straight up say that! It's helpful to be friends, for sure, but there’s more. We interrogate each other's ideas. We're not afraid to question each other about what we're thinking and make suggestions. I don't think either of us are defensive or particularly stubborn or one eyed about what it is that we're making. Mateo sees things in dance and choreography and spatial organization in particular that I sometimes might not notice as much. Those little adjustments that Mateo suggests are super helpful. He lends a whole other visual element to my work. He’s designed costumes and, you know, other kinds of set pieces. It's multi-dimensional. Matteo’s offerings push my work in new directions.

ML: Same thing [for me]. Lee brings things to the work that I'm looking for but cannot see for myself. It always fascinates me how he brings possibilities I never expected with the work. Sometimes, I’ll fabricate a sculpture that I imagine will be moved like this. But then Lee goes like this. And that's something that I don't expect. I believe in energies, and I believe in frequencies. Sometimes, you connect immediately with people, and sometimes you don’t. Then, it's hard for you to communicate. And in collaborations, that's reality. Sometimes it can work, sometimes it doesn’t. But I believe that when you're meeting someone, and you're starting to work with them, you just need to be open and try not to control everything. You need to lose control, let yourself go, and see what happens. I think that's the most powerful meaning of the collaboration. Let yourself go. I love that!

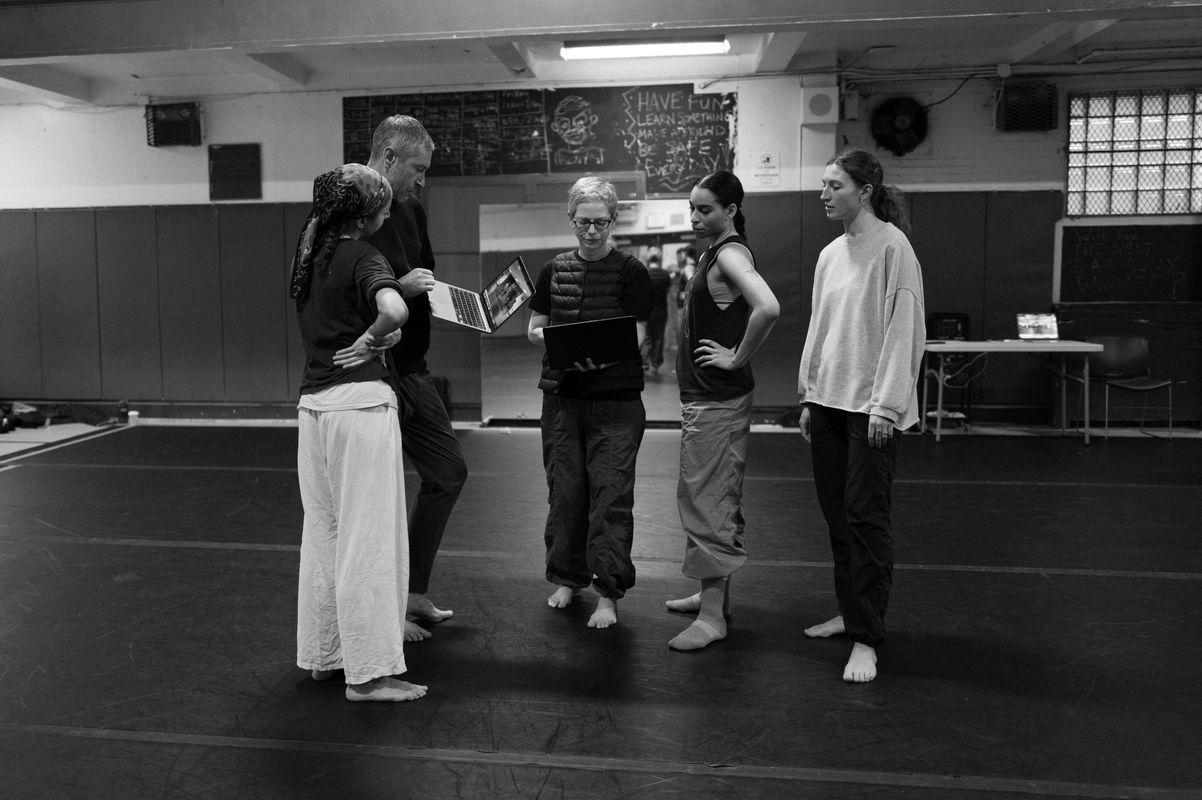

Let’s shift to talking about “Time again.” How has your collaboration on this piece been par for the course for you? How is it different?

LS: Well, firstly, the situation is different! We haven't been in the same place until a month ago. I went to Bogota to visit Mateo, and by that point, the sculptures had already been fabricated and were being shipped here. So all of our communication was through text, voice messages, and calls. So it's been different, this process. But we've been in regular contact and exchange images (Mateo sends a lot of reference images). Not being in the room together has presented its challenges, but it’s nothing unsolvable because we know and have a history of how each other works. We could take our usual process into a remote setting, and it still functions. It’s really actually quite great to know that we can still collaborate so closely while so far away.

ML: I think [the distance] started a conversation of revisiting works–like going back in the past of a previous work that we felt was too early or wasn’t being understood at the time. I believe that when you’re starting a new project, you need to go back and revisit your notebooks. Revisit the works, and pull an old idea that was sitting there instead of creating something new every single time. In the contemporary world, you feel everything needs to be new and new and new. But sometimes you need to revisit things and make them fresh–like bring it fresh to the present. For example, being in a theater brings other elements that are completely new for me, like the music, the lighting design, and the timing of the piece. So that’s making it new for me. It’s fun.

I would say it must be so fun to still have new territory to go into together. After working together for so long, there's still new things to learn about each other and yourselves. Like even learning from your past selves!

ML: I truly believe we need to recycle not just our garbage. Separate plastic, separate cardboard. We need to recycle ideas. We need to recycle works instead of producing and producing and producing every day. Then, there is a natural connection with that. It’s your spirit. The same spirit from the past that you bring to the present.

LS: And you often talk about it in terms of collage, bringing in these existing pieces recycling or reusing them. I use that principle with my choreography. There are things in this work, movements I've taken from previous works and put them in a new context in this work. Certain structures that I feel like I wasn't quite done with and that I wanted to flesh out to see how it can progress.

Lee, you’re the third person who's ever been commissioned by TBDC outside of Trisha Brown. You talked about how you're trying to bring your own voice into it and bring your knowledge from having been mentored by Trisha, but not make it derivative of Trisha’s work. In the concept and creation of the piece, what was your initial process like?

LS: The concept came to me initially because there was a series of life events that were repeating. I felt like I was always in the same situation, but the context or time was slightly different. It made me think about time as cyclical. You return to these places that feel very, very familiar, but it’s not like a “deja vu” thing. It's like things are actually playing out in a very, very similar way. That was where I began. If the situation feels the same but is slightly different, how can I choreographically make that visible? I’d start by having a dancer do a short improvisation once, and everybody else would have to capture what they could and make a version of their own. And then, it got pieced together. So there were similarities in the kind of physicality or dynamic or direction and things like that, but it was all variations. Everything is its own version of the event. That’s a very specific example. In other ways, it's more structural. There's a revisitation of earlier material in the work that got reorganized. So we're seeing similar things, but they're playing out very differently. But I felt like there was some “me” missing in there. I needed to come back to this latest development and really choreograph some things that are much more me, as opposed to, you know, these collections of other things. So I felt like I needed to get a little bit more narrow-focused with what I had to offer this work, and that will always still be in conversation with Trisha's legacy. I have had a 15 year experience with the company and have worked with her directly. It’s been part of my training.

When you say there was some of “me” missing, what does that mean? How would you describe your style?

LS: A lot of conflicting things happen physically when I'm improvising or when I'm actually just choreographing set material. There are certain physical traits in me that people can see, and I think that carries through in my choreography–a personal kind of stylized choreographic element that comes through. But then I think, you know, I've also had other lineage and other influences in my dance life and career. So the work can't help but have all of these influences. I'm the product of all my choreographic parents.